Fashion is one of the world’s most polluting industries. Its operational model is so unsustainable that by 2030, retailers are expected to see a detrimental impact on profit and margins as the cost of resources rises. In this report, in partnership with the ReGain app, we explore the systemic change that needs to occur as fashion moves from a linear to a circular model.

Exploring the right materials to use and how to increase recycling, we also discuss how and why sustainability will increasingly become synonymous with a business’s long-term health.

Jack Ostrowski, founder and chief executive, ReGain app at Yellow Octopus

In this growing age of the ‘conscious consumer’ there is increasing pressure on retailers to address the hugely negative impact of our throwaway culture, and nowhere more so than in the fashion sector.

Textile waste is becoming a social problem not only in the UK but all across Europe. Our unwanted clothing is currently contributing towards the 300,000 tonnes of textiles going to landfill in the UK every year; the equivalent of 50 trucks’ worth of clothing per day. As much as 95% of the clothes thrown away could have been reworn, recycled or upcycled.

The retail industry has a responsibility to help address this – currently they make money from sales of products but have no responsibility for what happens to the items after they are sold and this needs to change. Changes in legislation around sustainability are also going to make retailers sit up and pay attention to the issue, something that is already happening in France where it will soon be illegal for companies to dispose of any excess stock in an unsustainable way.

We have already seen many large fashion retailers such as H&M and Zara introduce recycling schemes designed to incentivise customers to dispose of their unwanted garments in a more responsible way, and there are likely to be many more following their lead in the months and years ahead. Effective take-back programmes are at the heart of a successful circular economy model for fashion and retail, and every retailer has a responsibility to not only engage with take-back programmes, but to educate and incentivise their customers about textile recycling options.

Yellow Octopus, which works with the largest fashion retailers in the UK to find sustainable stock exit solutions for post-consumer textiles, is in a unique position to help address this problem and provide retailers with a simple way to engage in the growing circular economy of fashion. As participants of Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s ‘Make Fashion Circular’ and SCAP 2020 signatories we are committed to being part of the solution and to working with retailers to drive forward positive change.

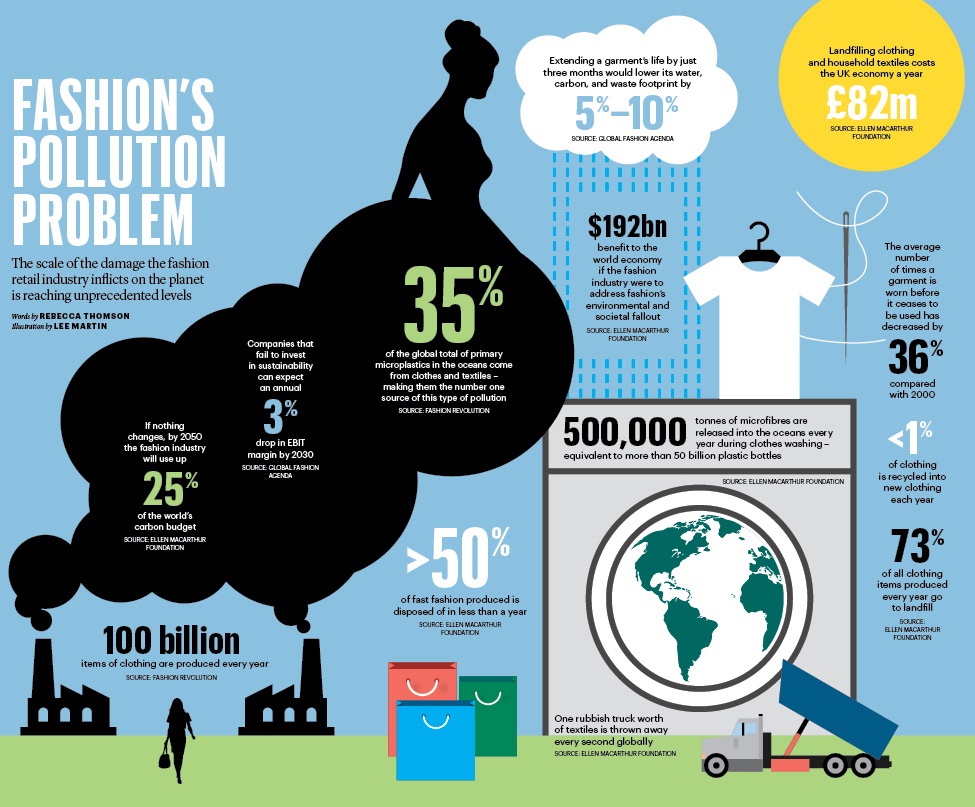

THE SCALE OF THE PROBLEM

Fashion is one of the world’s most polluting industries and its negative environmental effects are starting to dent profits.

As our infographic shows, the scale of the problem is significant – as is the opportunity to do things a different way. Click on the image below to see the full scale of the problem.

INTERVIEW: ELLEN MACARTHUR

Environmental thought leader Dame Ellen MacArthur is tackling waste and pollution in the fashion industry

Dame Ellen MacArthur has spent her working life tackling Herculean tasks. She first became known as a yachtswoman, coming second in 2001 in the formidable Vendée Globe solo round-the-world race at the age of 24 – the fastest woman and youngest-ever sailor to complete the race.

In 2005 she went one better, setting a world record by sailing around the world in 71 days.

It was that voyage, which required her to survive on the bare minimum of supplies, that sparked her interest in how the Earth’s resources are used. She spent the subsequent years travelling and learning about the global economy, and in 2010 launched the Ellen MacArthur Foundation with the goal of creating a circular economy.

Source: Getty Images

Since then, MacArthur has been busy. She has forged corporate partnerships, brokered UN agreements, addressed countless conferences and carved out a presence at the World Economic Forum meeting at Davos. The foundation has lobbied everyone from industry chiefs to world leaders, preaching the importance of a circular economy that makes better use of recycling, instead of relying on the continued production of environmentally damaging raw materials. Her work is behind much of the recent focus on plastic pollution, which has hit the headlines over the last few months, and she has convinced corporations from Unilever to Philips to sign up to her cause.

Fashion focus

Now, MacArthur is turning her attention to fashion – one of the world’s most environmentally damaging industries. In November 2017, her foundation published the A New Textiles Economy report as part of its Make Fashion Circular initiative. The report was launched in partnership with Stella McCartney, one of the initiative’s core fashion partners, and retailers including Burberry, Nike, Gap, H&M and Primark have all signed up to the initiative. MacArthur is after more, however, pointing out the entire system needs to adapt.

“The goal is to create systemic change,” she says. “It’s changing an industry, not a company. The only way we’ll make fashion circular is if the biggest companies choose to switch. One company can’t do it.

“We see this as a massive economic opportunity to build a system that works, plus a fashion industry that can run in the long term.”

If fashion fails to act, MacArthur predicts dire consequences: fashion will be responsible for a quarter of total carbon dioxide emissions by 2050 if nothing changes. Its use of resources will become more intensive as consumers buy more clothes, and, as global wealth continues to grow in markets from China to India to Brazil, more consumers will increase their frequency of purchase.

This will lead to higher plastic pollution from clothes made of petroleum-derived substances such as polyester. If fashion continues on this path, it will be responsible for the addition of 22 million tonnes of microfibres into the world’s oceans by 2050.

We see this as a massive economic opportunity to build a system that works, plus a fashion industry that can run in the long term

MacArthur, however, is upbeat about fashion’s propensity for change, and reports a can-do attitude among the retailers she and her team have spoken to so far: “We see a phenomenal amount of energy.”

Francois Souchet, who leads the Make Fashion Circular initiative, adds: “The reception to the report was extremely good. We were pleasantly surprised by the dynamism and willingness of the industry.”

Sustainability has serious momentum behind it, says MacArthur, and more and more consumers say it is important to them. Much of the most exciting innovation is coming from small and medium-sized brands and retailers: companies from Danish maternity and childrenswear brand Vigga to US label Nudie Jeans have started to lease clothing, which extends its lifespan, as well as adding repairs and recycling to their business models.

Fast fashion

Sustainable fashion is often still associated with premium brands, whose consumers can afford the higher price points. But from an environmental point of view, it is the mid-market and value sectors that could have the biggest impact, because of the volumes of new product they manufacture.

Even in this part of the market, Primark and H&M have both signed up to the Make Fashion Circular initiative, while another partner, Inditex, is upheld as a leader in the sustainability space for encouraging recycling in its stores in Spain.

A spokeswoman for Primark said it joined the initiative as part of its wider sustainability efforts: “As a participant, Primark will unite behind the three key principles of the initiative: business models that keep clothes in use; materials that are renewable and safe; and solutions that turn used clothes into new clothes.”

Leasing high-quality clothes is different from fast fashion. But no matter where you sit on the scale, you can think about where materials go

MacArthur says: “Primark knows that the linear business model can’t run in the long term. Some items of clothing by their nature cycle faster than others. You might have a jacket for 20 years – underwear, maybe not. When you produce faster-cycle stuff, think about the materials in it: could they be composted or recycled?

“The business model in a circular world is a sliding scale. Leasing high-quality clothes is different from fast fashion. But no matter where you sit on the scale, you can think about where materials go.”

Souchet adds that each business needs to solve the linear-model problem on its own terms: “Businesses need to figure out what their own answer will be. The main limit we have is imagination. Think about how your business could be part of the new system. We want people to find their own answers, so it’s also a question of empowerment.”

Collaboration and transformation

Souchet says that successfully moving fashion to a circular model will only happen if two things occur: first, collaboration is needed to achieve the systemic-scale change necessary; and second, every individual business needs to think imaginatively about its own place in the new system.

“We’re early in the process, but one thing we’ve seen is that there are two sides: first is collaboration to make sure safe methods are affordable. But it’s fundamentally an individual company journey. You can have partnerships, but it’s down to each company to transform the way they generate revenue.”

The current system can’t work in the long term

MacArthur says this strategy is not a choice, and for those who are not prioritising sustainability, she has a bleak prognosis. She says fashion cannot exist in the longer term in its current form, and that businesses will soon start to notice a detrimental impact on profits if they do not act. The costs of raw materials will keep rising as resources become scarcer, while other businesses cut their costs by extending the life of existing materials.

“It’s common sense,” she says. “The current system can’t work in the long term. It’s logical. There is definitely the impression from the industry there’s a need to change. Things will change.”

With MacArthur at the helm, change may be unavoidable.

WHAT ARE RETAILERS DOING?

There is a long way still to go, but retailers are stepping up their eco efforts, introducing sustainable materials and training designers in circular methods.

Adidas

In 2017 Adidas sold 1 million pairs of shoes made from recycled plastic – each pair prevents 11 plastic bottles from entering the ocean. It expects this to grow to 5 million this year.

Adidas uses Parley Ocean Plastic materials throughout its clothing and footwear collections,

Nick Maass, Adidas’s global spokesman for its educational programme, Run for the Oceans, said: “The project was started three years ago with one shoe, and we continued on the journey after seeing an incredible response from the outside world. It encouraged us to push further, and we started to really scale it up last year. It’s not just about product, it’s also a holistic, educational programme.”

Asos

Asos has a sustainable sourcing programme whose most recent announcement was that it would stop using mohair, silk or cashmere in its designs, and by 2020 has pledged to reduce the carbon, water and waste footprint of its own-label clothing by 15%. By 2025, it plans to use 100% sustainable cotton in its products.

It has also signed the Global Fashion Agenda’s pledge to accelerate the transition to a circular fashion system, meaning that by 2020 it will have trained all of its design and product teams on circular principles. It plans to launch a recycling programme by 2020, and is working to increase the amount of recycled materials in its ranges, although it does not appear to have a formal goal. In June 2018, it announced it is launching a sustainable fashion training programme in partnership with the London College of Fashion.

Its Eco Edit sells 36 brands, with an annual sales target of £30m by 2020. Products in the Eco Edit must contain at least 50% sustainable fibre.

H&M

H&M is working towards a series of goals as part of its global sustainability strategy, including using 100% sustainably sourced cotton by 2020, using 100% recycled or other sustainably sourced materials by 2030, collecting 25,000 tonnes of unwanted garments each year through its instore garment collecting service by 2025 and becoming 100% climate positive by 2040, which means removing more emissions than its operations produces.

Levi’s

Levi’s is focused on four key areas – water, chemicals, carbon and people. For water, the goal is to make 80% of products with its water‐saving Water

It is reducing its emissions by 25% (from 2007 levels) and using 20% renewable energy by 2020. In 2011, it launched Worker Well‐being, an initiative that focuses on financial empowerment, health and family well‐being, and equality and acceptance.

By 2020, the goal is for 80% of product to be produced by suppliers that are implementing Worker Well‐being programs, reaching more than 200,000 workers.

John Lewis

In June 2018 John Lewis announced a pilot “buyback” service for unwanted clothing, which allows customers to have unwanted clothing that was purchased from John Lewis collected from their home. Customers are paid for the clothing, which can be in any condition.

John Lewis is using past-purchase data to determine what shoppers have bought over the past five years from the department store chain, and values the items on an app. Collections are made when customers amass a minimum of £50 worth of product and vouchers equivalent to the value of clothing are emailed in return.

Kering

Kering and H&M were the only two fashion brands to appear on Corporate Knights’ Global 100 Index in January 2018, an annual index of the world’s most sustainable corporations. Kering, which owns luxury brands including Gucci and Saint Laurent, was ranked 47th, compared with H&M at 57.

Kering has a three-pronged strategy that includes a goal to ensure 100% traceability of raw materials by 2025. One its brands, Gucci, recently unveiled online content platform Gucci Equilibrium, which explores sustainability issues and explains its wider plans.

CHANGING THE CULTURE

One of the biggest challenges fashion businesses face around sustainability is internal mindset and culture.

For a business to become truly sustainable, it cannot simply pick and choose practices that are easy and convenient to implement – every part of its operations needs to change. To tackle this challenge properly, a complete shift in business culture is required form the outset. In fact, it should be the first step in creating a new mindset that puts sustainability at the heart of all decision-making.

Michael Kobori, vice-president of sustainability at Levi Strauss & Co, says the business has made the issue integral by placing individuals with responsibility for sustainability in key teams throughout the company.

“Our sustainability team is embedded in our supply chain organisation, where we have our greatest environmental and social impact,” he explains. “We work every day with our colleagues and suppliers to reduce those impacts. We also have an internal sustainability board, which oversees how sustainability is integrated across our business – everything from design to marketing, finance and human resources.”

Kobori adds that Levi’s works hard to develop a flexible,“start-up” mentality, despite its 165-year history. This has helped it to adopt sustainable approaches more quickly.

“Behaving as a start-up means that innovation drives everything we do,” he says, “from implementing cutting-edge design techniques to inventing more sustainable ways to make our products, to open-sourcing our sustainability innovations to the rest of the industry.”

Our sustainability team is embedded in our supply chain organisation, where we have our greatest environmental and social impact

Michael Kobori, vice-president of sustainability, Levi Strauss & Co

Kobori adds that it was Levi’s traditional values that helped the business to embrace its current focus on innovation and sustainability: “Over the years, our values of empathy, originality, integrity and courage have led to our philosophy of profits through principles.

“This means that by doing the right thing, business success will follow. This mindset provides a strong cultural foundation for sustainability.”

At H&M group, where the goal is to use only recycled or other sustainable materials by 2030, the buy-in of staff has become imperative.

“Colleague engagement is key to ensuring that sustainability is rooted in all aspects of our business,” says Giorgina Waltier, H&M’s sustainability manager for the UK and Ireland. “We are continually working to ensure that all our colleagues in all functions have an understanding of why sustainability is so important to our business and, crucially, how it is relevant to the job they perform.”

Waltier adds that every person working in the business needs to understand how they are making a difference: “Making sustainability relatable and making colleagues feel that they have the ability to create an impact is the key.”

Eric Sprunk, chief operating officer at Nike, said at the Copenhagen Fashion Summit in May that the sportswear giant had to undergo “a bit of a journey” to arrive at its current position on sustainability.

“In the late 1990s, the headlines were about our labour practices and not much else,” he recalled. “We were appropriately criticised for not listening and not caring.”

Sprunk added that, at the time, Nike saw compliance to ethical standards only as a risk, which was at

odds with the need for business growth. The first step in changing this view was disclosing the locations of its factories.

“It was a watershed moment, helping us pave the way for collaboration,” he admitted.

But Sprunk added that another development had an even greater effect: “The most powerful shift we could make was changing our culture.”

The most powerful shift we could make was changing our culture

Eric Sprunk, chief operating officer, Nike

The sourcing and manufacturing teams at Nike are responsible for the environmental impact of their decisions, including the health and well-being of the brand’s 1 million workers across the supply chain. Environmental and human rights compliance now sits with Sprunk’s team, while the chief sustainability officer, Hannah Jones, focuses on innovation and sustainable business models.

Sprunk said that while there may be some quick and easy wins for businesses that are in early stages of tackling the issue, there is no point doing a half-hearted job: “Sustainability has to be the new frame through which to view every innovation and every business model.”

Sarah Ditty, head of policy at Fashion Revolution, a not-for-profit movement that campaigns for greater transparency in the fashion industry, says change needs to be led from the highest levels of the business: “It’s pretty straightforward. Brands that are doing well are those with a commitment from the top. The CEO, especially, needs to be interested and committed. That’s absolutely critical.”

But the impetus for change does not always have to come from the boss. Ditty cites Primark as a good example of a retailer whose ethical trading team is leading a cultural shift.

“It has a really active and increasingly robust sustainability and ethical trading team,” she says. “A lot of progress Primark has made has stemmed from that team and their ability to be able to convince, and really make the business case internally to those at the top.”

Once a business has tackled its internal culture, it is then time to communicate the value of ethical retailing to shoppers. And as Jack Ostrowski, founder of recycling app ReGain, notes, when businesses set about communicating their brand values to customers, it is crucial to keep things simple.

“Applying simplicity to everything is a big part of [growing awareness of sustainability],” he says. “Consumers need things to be convenient and they need them to be easy to use.”

Top tips for building a sustainable culture

1 Make all teams accountable Ensure every team is aware of the requirement to make decisions that fit with a wider circular model or sustainable approach. Make it part of their KPIs and daily responsibilities to ensure it is embedded at every stage of the decision-making process within a business.

2 Commit from the top As with any wide-scale change, shifting to a circular business model will not happen unless the motivation to do so is led from the top of the organisation. From there, the plan to embed sustainability at the core of the organisation will spread outwards.

3 Take one step at a time Moving to a circular model is a big change, requiring businesses to acknowledge and celebrate the small steps on the way and communicate seemingly minor achievements to the rest of the business. Progress at the beginning may be slow and come in small, incremental steps.

4 Put a strong team in place to lead While the whole business needs to think sustainably, the shift to a circular future will need strong leadership and possibly a central sustainability team with high-level support. This team will likely drive large amounts of change early in a retailer’s journey.

RECYCLED MATERIALS

There is a large amount of innovation occuring in the recycled materials space. What options are avilable to retailers in 2018?

Less than 1% of material used to produce clothing is recycled into new clothing and just 13% of the industry’s total material input is in some way recycled after it is used for clothes, reports the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

And more often than not, the little that is recycled goes on to be used in other sectors, such as in insulation and mattress stuffing, rather than being reused in the fashion industry. However, slowly but surely, retailers are recognising the importance of “closing the loop”.

“The idea of a circular textile economy has shifted from an interesting picture you might see on a slideshow at a conference to a something that is actually happening,” explains Sally Uren, chief executive of sustainability initiative Forum for the Future. “In the next five years, we’ll see a much more widespread adoption of takeback schemes and that is because of the hard fact: we are running out of materials.”

We’ll see a much more widespread adoption of takeback schemes because of the hard fact: we are running out of materials

Sally Uren, Forum for the Future

A new wave of recycled textiles is helping fashion to close the loop, with materials made from waste products becoming a key area of innovation. Swedish giant H&M group, known for its ambitious sustainability targets, experimented with Econyl, a regenerated fibre that uses waste nylon from landfill and from oceans, in its environmentally friendly collection Conscious Exclusive earlier this year.

Last month, meanwhile, plus-size retailer Simply Be unveiled a denim range made from a blend of cotton and a fibre made from recycled plastic bottles, citing the “war against plastic” as the inspiration for the collection.

Animal alternatives

Others are experimenting with replacements for animal products. Over in the US, sustainable materials start-up Bolt Threads has created protein-based synthetic spider silk Microsilk and Mylo, a leather grown from the root structure of mushrooms.

Another sustainable initiative working to transform waste products into biodegradable materials is San Francisco-based Mango Materials, which produces a biopolymer from methane gas.

“In basic terms, we take methane gas, which is made from a lot of things, such as landfill and agriculture, and feed it to bacteria that love methane,” explains Mango Materials vice-president of customer engagement Anne Schauer-Gimenez.

“The bacteria convert the methane into a biopolymer that can be used for a number of applications, such as glasses, phone covers or beauty packaging. However, within the last year the story around sustainable fashion has really grown and one of the main areas of interest now is using the biopolymer as a replacement for polyester.”

By 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the sea

Anne Schauer-Gimenez, Mango Materials

She adds: “There is a push for transparency in lots of industries, from packaging to textiles. One of the key statistics that has really hit home [also from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation] is that by 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the sea.”

Clothing conundrum

Making textiles from recycled clothing remains more of a challenge – although the industry’s innovators are devoting time, money and brain power to creating fabrics that can be used time and time again.

“Garments are often made out of many different kinds of fibres and it’s not yet possible to separate some of them at a large scale before spinning a new yarn,” explains Anne Karin, corporate sustainability manager at Swedish womenswear retailer Lindex, which aims to have 80% of garments made from more sustainable sources by 2020. Lindex also has a long-term ambition to increase the amount of “closed loop” fibres used within its products.

“Clothing containing Lycra can be difficult to recycle – although with research and development, we are hoping to find a solution in the near future. There are now ways of chemically recycling fibres and separating cotton from polyester. However, these methods are not yet scalable.

“Another challenge is that often the chemical content of garments cannot be determined effectively, so it is hard to decipher exactly what is in the final material.”

Plant life

Austrian fibre giant Lenzing is one business leading the way. It launched sustainable cellulose fibre Refibra in 2017. Made from recycled cotton scraps and wood pulp from sustainably managed forests, Refibra has been used by brands including outdoor and sustainability specialist Patagonia and luxury designer Mara Hoffman.

There are now ways of chemically recycling fibres and separating cotton from polyester

Anne Karin, Lindex

Recycling technology specialist Renewcell is also working to create a circular fashion industry. It receives used garments with a high cellulosic content at its plant in Kristinehamn, Sweden, which are then shredded and turned into a slurry. Contaminants are separated from the slurry, before it is dried to create a pulp that can be used in textile production. H&M took a minority stake in Renewcell in October last year.

“We’ve been very encouraged when talking to brands and retailers, because the interest in circularity and sustainability has really increased over the past two years,” explains Renewcell’s head of communications Harald Cavalli-Björkman. “There’s a growing awareness that this industry is wasting a lot of materials that could be used again.”

Closing the loop in the fashion industry also depends on making use of the many tonnes of unwanted fashion thrown by customers each year. UK households alone sent 300,000 tonnes of clothing to landfill sites in 2016, the Sustainable Clothing Action Plan reported last year. Retailers such as H&M and Zara are stepping up in-store recycling programmes. Etail giant Asos has pledged to introduce a garment-collection scheme and recycling programme for customers in the UK and Germany, its largest markets, by 2020.

Lindex has also introduced textile recycling in its three biggest markets and aims to roll it out fully 2020.

The ReGain app, which enables shoppers to recycle clothing in return for discount vouchers, is gaining traction among consumers and brands.

There is a huge amount of work to be done, but there is also a lot of opportunity and innovation in the recycled materials market. The biggest brands and retailers must ensure they are involved.

REGULATION'S ROLE

What role should governments and policy play in heralding fashion’s sustainable future?

As it stands, sustainability in the UK is largely unregulated by policy.

Duncan Reed, legal director at law firm TLT, explains: “Sustainability in fashion is largely non-regulated in the UK. It is typically left to self-regulation through the use of standards and logos that retailers and manufacturers can voluntarily meet. It’s the carrot rather than the stick approach.”

“The sustainability sector is perhaps one of the few areas where companies self-regulate above legislation,” says Diana Verde Nieto, co-founder and CEO of Positive Luxury, the certification body that awards the “Butterfly Mark” to sustainable luxury businesses. “We are seeing this more and more across fashion and beauty industries. This self-regulation then pushes the government towards wider legislation – for example, micro-bead banning was firstly adopted by brands, and then legislated.”

The government could be raising taxes on using virgin materials and cutting taxes on recycled materials

Sarah Ditty, Fashion Revolution

This can be seen in increased government action as awareness around issues of sustainability grows. The ban on the sale of cosmetic products containing micro-beads came into force in June 2018 with the aim of reducing plastic pollution in waterways. It followed The Modern Slavery Act, which came into effect last year, and stipulates that all businesses must demonstrate what they are doing to ensure there is no slavery in their supply chains. Other measures such as regulation on single-use plastics, such as packaging and cotton buds, is also being mooted by the government.

Government attention

Self-regulation may not be the case for much longer, however: fashion is starting to attract government attention. In June, the government’s Environmental Audit Committee launched an inquiry into the social and environmental impact of disposable “fast fashion”, and the wider clothing industry. A date for the results of this is yet to be announced, but the inquiry willl take submissions until September 2018, and could result in increased regulation.

This increased regulation is something Sarah Ditty, head of policy for sustainability campaign group Fashion Revolution, says is much needed in several specific areas: “We absolutely see it as a place for government and local authorities to drive change. They should be making companies accountable for their waste, both pre- and post-consumer.

“There should also be extended producer responsibility legislation – a form of product stewardship. This makes manufacturers and brands responsible for waste and packaging waste, both before it hits the shop floor and potentially after.”

The recent ban on micro-beads shows that sustainability is becoming a more regulated issue and how quickly the law can change

Duncan Reed, law firm TLT

It is not just about regulation, however, Ditty argues: “The government could be investing in research and infrastructure to reduce waste. That would help deal with it. They could be raising taxes on using virgin materials and cutting taxes on recycled materials, as well as creating products that are recyclable. They could invest in recycling technology and infrastructure, and make it easy for customers to recycle clothing and textiles.”

Mandatory traceability

Simone Cipriani, CEO and founder of the UN’s Ethical Fashion Initiative, adds that greater accountability is needed in relation to labour welfare: “Traceability should be compulsory, and businesses, wherever they are based, are accountable for what happens in their own supply chain. Companies must have a structure in place to ensure that in their supply chain, these violations of human rights related to labour, don’t happen.”

The launch of the government inquiry could bring about a rapid acceleration in these areas, and Reed notes that, once complete, the inquiry could lead to swift, significant change: “The recent ban on micro-beads shows that sustainability is becoming a more regulated issue and how quickly the law can change – if something is deemed to be a significant problem. If you apply that same speed to anything that comes out of this consultation, there could be significant changes quite quickly.”

European initiatives

These are early steps in increasing regulation across the fashion spectrum, and globally more initiatives are being introduced to counter the impact of fast fashion. The European Union is leading the way forming policy and encouraging change – for example, through the European Clothing Action Plan, which focuses on sustainability in fashion, and encourages businesses, brands and retailers to develop a circular economy within their companies.

As such, campaigners are voicing concerns over the potentially negative impact of Brexit on the UK’s sustainable policy.

“Brexit poses a possible lowering of standards,” says Cipriani. “The EU has a wide framework of action on sustainability, and has undertaken an ambitious programme to define systems of traceability in the fashion supply chain and to hold European companies accountable for that. The fact that the UK has distanced itself from the EU could imply that the UK is not part of that change.”

“European legislation, in some areas, is ahead of the UK and, in some instances, also the US,” adds Verde Nieto. “As Brexit approaches, our laws will need to be updated and hopefully we will come together as a nation in order to lead the way in this area.”

A NEW BUSINESS MODEL

What does the ideal circular model look like?

Moving from a linear to circular model is an enormous job. Clothing recycling will need to be drastically increased; fashion’s reliance on raw materials will need to be reduced. While it’s undeniably important to find more sustainable ways to produce cotton and other raw materials, it is crucial is that the industry finds ways to use less of them. At the same time, increasing its use of recycled materials will reduce the huge volumes of clothes that are sent to landfill every day.

As the infographics above show, a closed loop system with reduced levels of raw material inputs is the only way to achieve the drastic reduction needed in fashion’s environmental footprint, from chemical waste produced during the manufacturing process to the large volumes of post-consumer, non-compostable waste the industry sends to landfill.

These changes are complex, difficult, require cross-industry collaboration and in the short term are potentially costly. But they are likely to be necessary for any brand wanting to be here in the future. Fashion’s current operational model is unsustainable in the long term, and as labour and resource costs rise, the industry will need a new model to protect profits and remain relevant with increasingly eco-minded consumers.